Author: Nicole Olynk Widmar, Associate Head and Professor, Purdue University, Department of Agricultural Economics, and Carson Reeling, Associate Professor, Purdue University, Department of Agricultural Economics

There’s lot of demand for social action to reduce carbon emissions and for agriculture to have a role in this. There are also many challenges, political and otherwise, with the functionality of these non-regulatory voluntary markets; the science on all of this ‘carbon stuff’ is not settled by any stretch of the imagination.

Challenge: How much carbon is actually sequestered? It is very difficult, costly and time intensive to actually measure the amount of carbon that is sequestered in any given soil/field. The practice that is focused upon in conversation today is utilizing cover crops. There are indeed a variety of benefits to cover crops, including sequestration of carbon, but the amount of carbon actually sequestered varies WIDELY from basically zero to one metric ton per hectare per year, depending on the crop, the production practices, the cover crop, where you are and a variety of other factors. If we are going to have any confidence regarding the amount of carbon embodied in these offsets, then we need to measure it – but that’s expensive and time consuming, so we don’t do that. Instead, we determine the carbon we’d expect to be determined using models; the jury is still out on how accurate some of these models are.

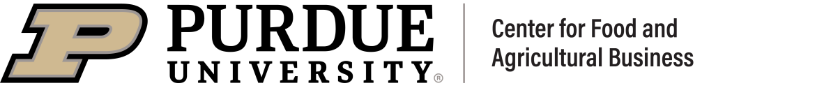

Challenge: Additionality, or simply stated, we don’t want to pay people for nothing. If you’ve already revealed that you will sequester carbon for free, then we don’t want to pay you to do practices you would have done anyway.

This “already doing it” acreage is making credit buyers and society at large wary. If members of the general public are genuinely interested in carbon emissions reductions, then they are concerned that the reductions aren’t ‘real’ in the sense that no additional carbon emissions have been abated.

If there are essentially worthless offsets being promoted which are later discovered to have zero value because there is a violation of additionality, and if enough people find out about these violations, then nobody will want to buy … which is a clear challenge for this non-regulatory voluntary market.

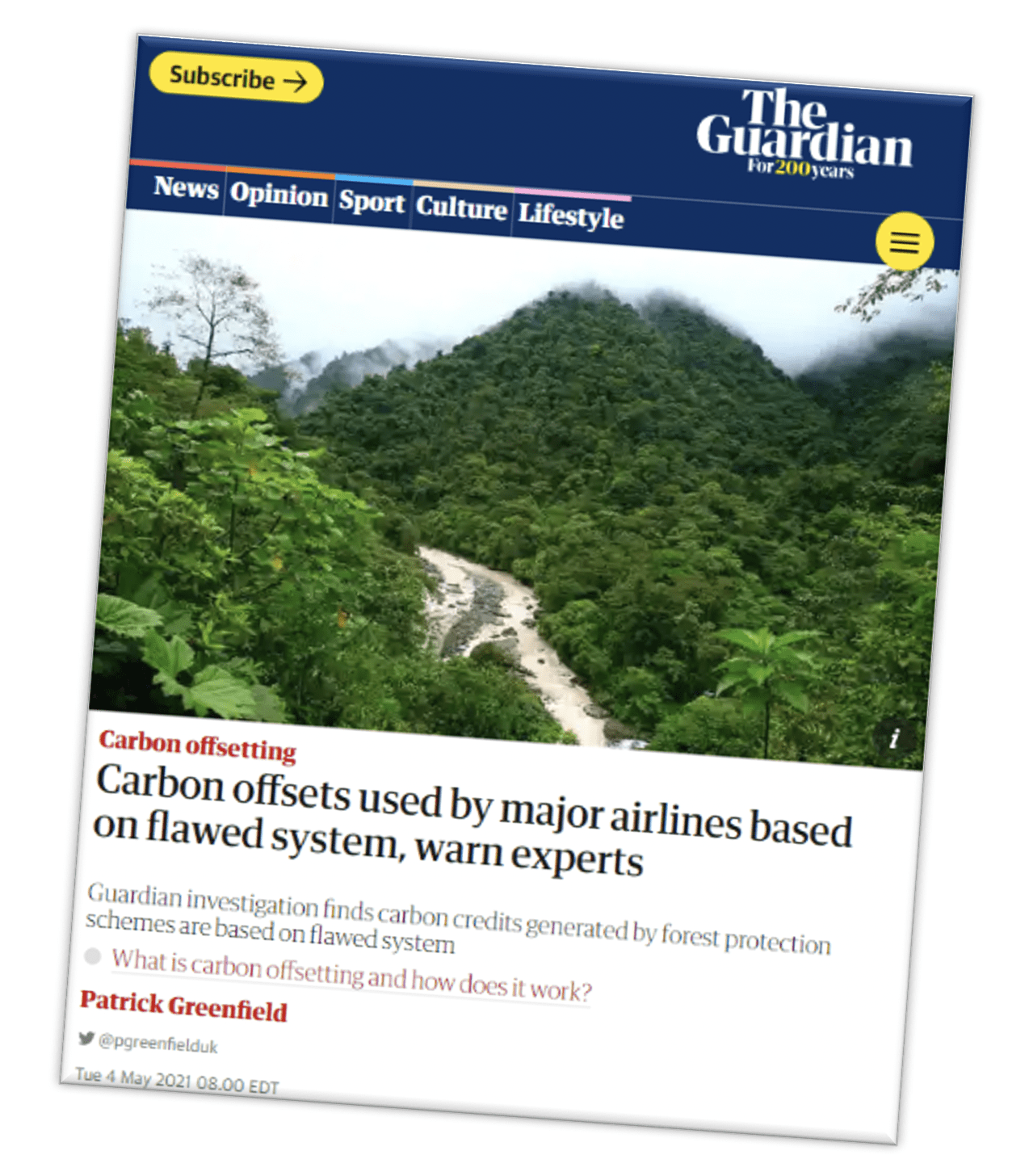

Challenge: Permanence. Sequestering carbon in working agricultural lands presents the challenge that the timelines on sequestration are decades long, and a single disturbance of the soil carbon stock can release a lot of that sequestered carbon. The challenge here is that if you disturb the soil, you release the stored carbon, which is a clear problem for those who may have sold that sequestered carbon in the form of an offset.

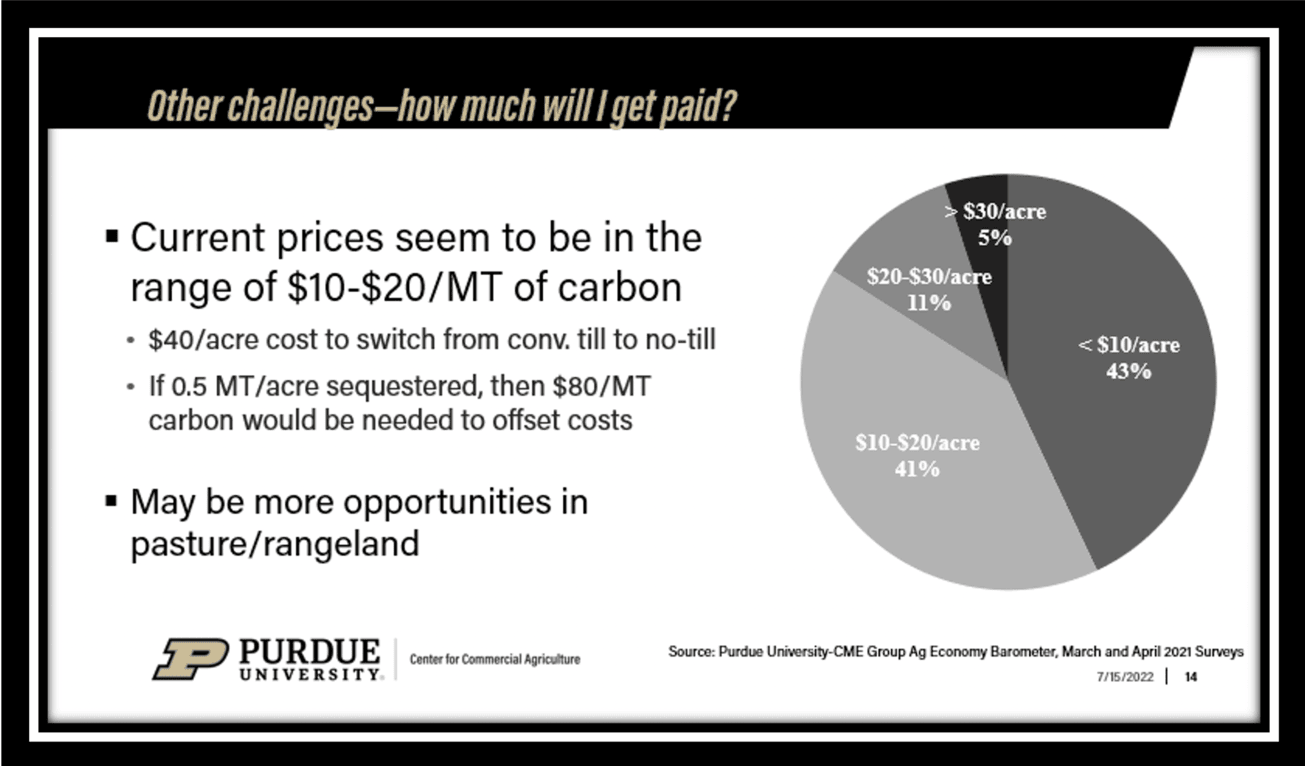

Challenge: Economics. Consumers are willing to pay for sustainability — they like labels that indicate that what they’re buying is good (or at least less bad) for the environment. But that value for sustainability by consumers is not necessarily trickling down to farmers. The majority of farmers surveyed did not pay enough to compensate farmers.

Challenge: Long-lived contracts and negotiation periods. Negotiations are taking years in many cases, and even once the contract is signed, it has an ending period that is 1-20 years away. It is very unclear what happens to the carbon sequestered in the year after the contract period ends … if the practice ends, then the carbon sequestered is released? There is a lack of clarity about what happens at the end of these contracts.

Challenge: Liability for Reversal/Impermanence. There is a lot of uncertainty surrounding what happens in the event of a one-time event and/or upon permanent abandonment.

Taken all together, there remains interest from all parties in carbon abatement programs (or markets, if you wish), but there also remains a number of challenges to be tackled.

ConsumerCorner.2022.Letter.32