Without doubt, COVID-19 has altered nearly every aspect of daily life. While its impacts are undeniable, these impacts are not uniform. Do you use public transportation to access groceries and essential items? Do you have access to a personal vehicle and a nearby supermarket? And perhaps the most debated conundrum for agriculture and food supply chains…

Does your supermarket have the exact items you want to purchase when you want them?

A full-page ad in the Sunday New York Times by the Tyson Foods board chairman John Tyson in April 2020 entitled “The Food Supply Chain is Breaking” elicited national concern and corresponding media response. Tyne Morgan followed up with a piece aptly entitled, Is the Food Supply Chain Actually Breaking? in which she conducted an interview with Dr. Jayson Lusk.

“I have a little different view,” says Jayson Lusk, a Purdue University agricultural economist. “I think by and large, throughout this crisis, the food supply chain has responded remarkably well. Yes, we had a short period for some grocery store shelves were empty, but by and large, food was available. It might have been a different variety or different brand than you’re accustomed to buying. But the foods system responded remarkably well to a completely unexpected and unprecedented event. We certainly have some very serious challenges coming up in the meat sector, but that doesn’t mean the entire system is broken.”

What Did the U.S. Public Have to Say?

We’re all impacted heavily by our own echo chambers, and part of understanding our consumers is to free ourselves from our own silo of concern to hear about the concerns of others. We collected data June 12–20, 2020 about impacts of COVID-19 on U.S. households as part of a study of perceptions of COVID-19 with respect to personal values/behaviors associated with reopening. Last week’s A Tale of Two Petes…Purdue Pete and Pistol Pete (OSU) Territories: COVID-19 Impacts and Mask Usage Beliefs and the letter from July 27th, Human Behavior, Beliefs and Practices in the COVID-19 Era, drew insight from this same study.

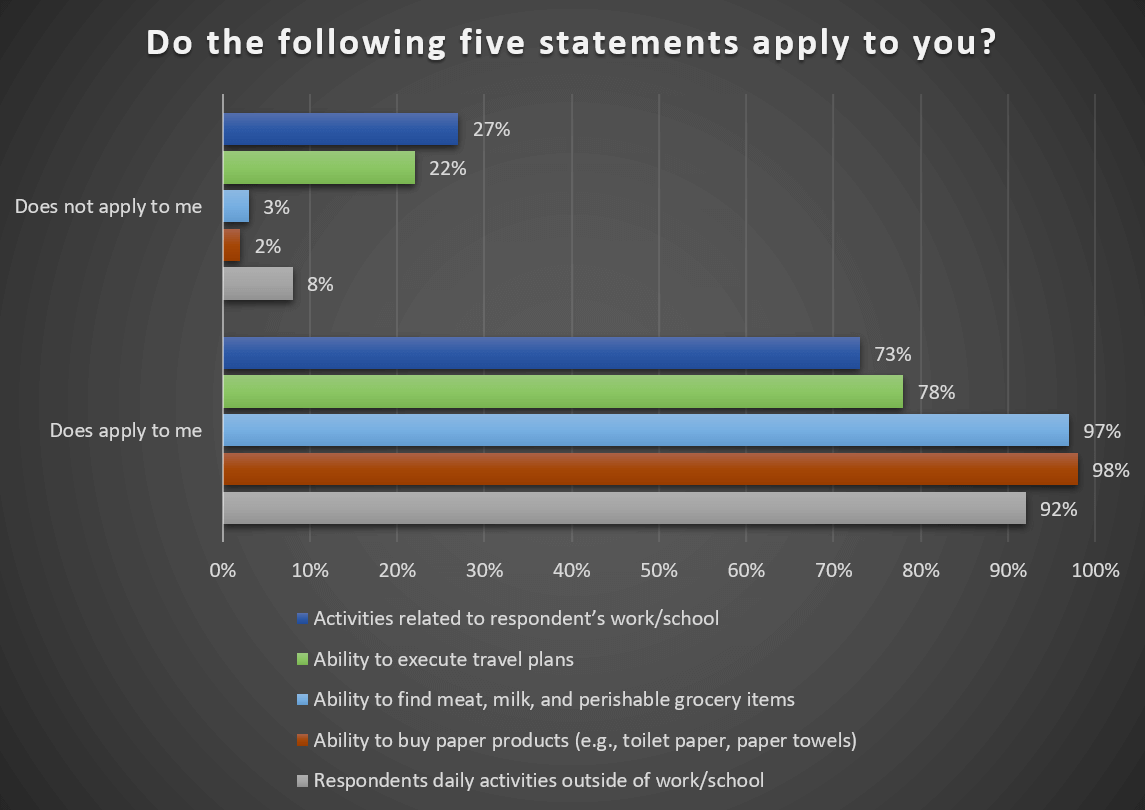

As part of this study, we measured the self-reported household-level impacts of COVID-19 using five impact statements on 1,198 households in a representative sample of the U.S. First, we asked respondents to indicate if each of the five statements provided applied to them.

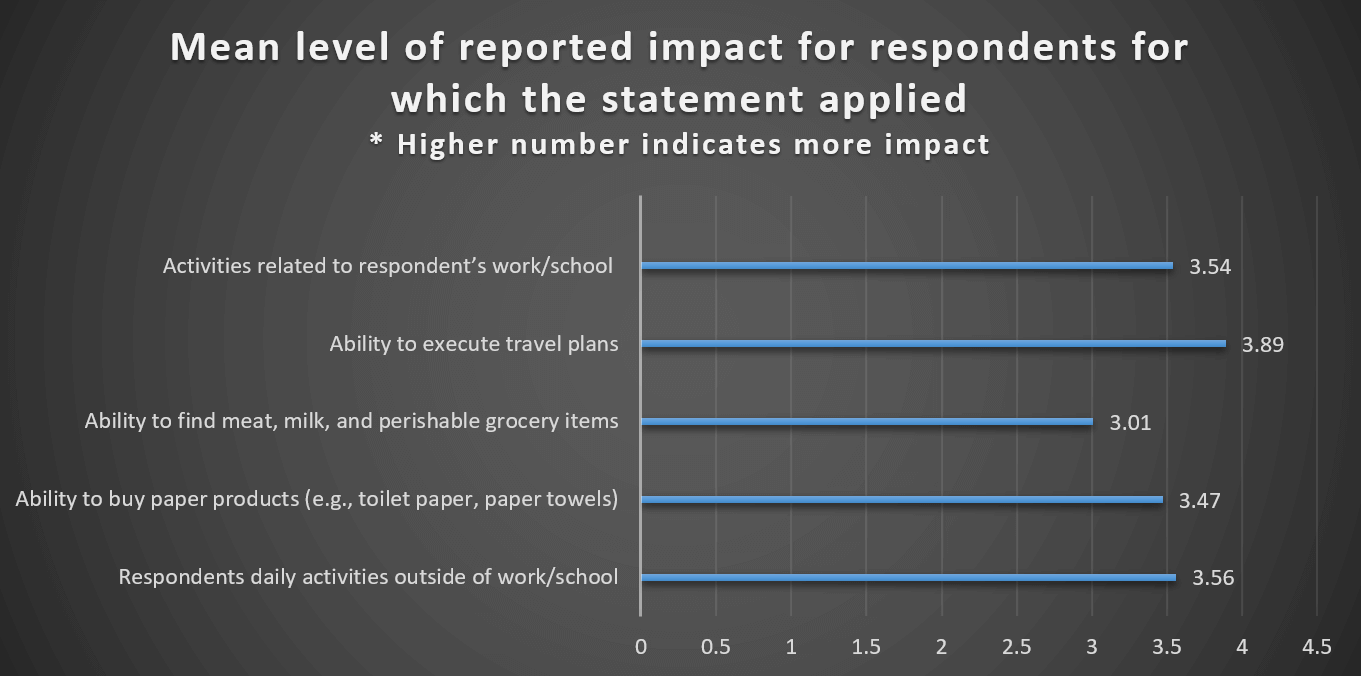

Next, we asked those who indicated that the statement applied to them to rate it on a scale of (1) Not Impacted to (5) Impacted. We expected the ability to locate meat, dairy and perishable foods to be rated as extremely high in U.S. households. It was not. In fact, it was the 5th most impacted among the 5 statements provided to respondents. One could argue about the statements presented to respondents. However, the fact remains that among the options presented, the category meat/milk and perishable foods was statistically – and practically – last in self-reported impacts.

In a Nut Shell: U.S. resident reporting of COVID-19 impacts suggests availability of perishable groceries (including meat and dairy) was less impacted than paper products, daily activities, travel plans and school/work activities.

Our Take…

Indeed, we faced challenges getting fresh dairy products and meat products into supermarkets fast enough to supply the rapid increase in demand of shoppers as they headed home to quarantine for a (then) unspecified amount of time. People went to the supermarket and could not get what they wanted. This really happened, and it was only a few weeks ago in many locales. It may indeed happen again. Dairy plants struggled to process the rapid shifting demand for products for home consumption versus making products for schools and food service. Meat plants were shut down as they faced outbreaks among workers, leaving livestock stranded on farms with no processing capabilities to be found elsewhere. These impacts were severe and very real. We do not intend to downplay the very real pain felt by agricultural industries. Meat industries, in particular, have suffered significantly to keep up with demand and there have been negative impacts throughout that supply chain at various times throughout the past several months.

Food for thought: Knowing what we know now, one may suggest that agricultural and food supply chains do so some introspective thought about resiliency versus redundancy. To what degree have we lost resiliency in the system by attempting to reduce redundancies and gain efficiency?

Taking all of the evidence together, and with the benefit of time (penning this letter in late July, as opposed to April), the food system in the U.S. has proven to have more resiliency then it was given credit in some of the earlier days of the COVID-19 lockdowns. Granted, that does not mean there isn’t room for improvement by firms involved in the food chain; there is always room for improvement, and many firms are making investments in resiliency already. That also does not mean that there isn’t room for the possibility of regulation and/or legislation to force practices/investment to improve resiliency. There were rough days. Indeed, there were times when shoppers couldn’t get what they wanted and there were times when there was obvious cause for concern as the system strained to keep up.

While everyone has faced, and continues to face, pressure in the COVID-19 economy and era, the food system in the U.S. has provided safe and (mostly) plentiful product (mostly) in the locations where it was demanded and (mostly) at the time that it was demanded. At least our data suggests that respondents, in their self-reported data, were reporting relatively less impact from perishable food product availability than from the other statements provided.

ConsumerCorner.2020.Letter.13