Article

Article

Hammond, J.S., Ralph L. Keeney, Howard Raiffa. (2006). “The Hidden Traps in Decision-Making.” Harvard Business Review.

Reviewers

Dr. Nicole Widmar, Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics

Dr. Michael Boehlje, Professor Emeritis, Department of Agricultural Economics

Summary

Poor decisions are often a result of the way decisions are made. In this article, Hammond, Keeney and Raiffa talk discuss the ways that the human brain can sabotage decisions through a series of psychological traps. They describe the ways that decision makers can ensure their major decisions are sound.

What this means for food and agribusinesses

Decisions, decisions. Every day you make decisions that are seemingly small and insignificant. What to wear? What to have for breakfast? Where to park today? These seem like minor decisions that should be easy to make and consequences of which are likely not overly (relatively) large. However, some of the most powerful, and in some cases consequential, decision makers among us have increasingly subscribed to a minimalist approach to decision-making.

You might ask why someone whose life is tasked with making decisions that impact many (if not all) of us, including Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs, and Barack Obama, would avoid making decisions daily about small everyday matters, such as what to wear. The answer is well supported by research surrounding decision fatigue. Researchers designing survey instruments, for example, recognize the potential for decision fatigue in respondents and thus limit survey length (or complexity) to facilitate collection of high-quality data. If one limits the amount of decision-making in survey administration to facilitate respondents making careful decisions without experiencing fatigue that impacts decision-making, it is reasonable to extend such thinking to one’s own daily decision-making. Making decisions is indeed fatigue inducing, so the minimalist approach simply addresses the known fact that decision-making resources are fixed by refusing to use that scarce resource on daily decisions that arguably matter less than others.

Those among us who seek to simplify daily decision-making – “daily decision minimizers,” you might call them – are saving their efforts for the big decisions. We try hard to make the best decisions, especially for the big decisions, by clearly defining the problem or issue, identifying alternative solutions, collecting the right information, and analyzing the costs and benefits of the alternative solutions. Furthermore, many among us are increasingly focused on and dedicated to identification of more creative or “out-of-the-box” alternative solutions.

Certainly, decision-making in the business world today does not suffer from a lack of attention or effort on critical decision-making. But as John S. Hammond, Ralph L. Keeney, and Howard Raiffa point out in the Harvard Business Review, “In making decisions, you may be at the mercy of your mind’s strange workings.” Poor decisions can result from a well-structured process. The fault is not the process. “The way the human brain works can sabotage the choices we make.”

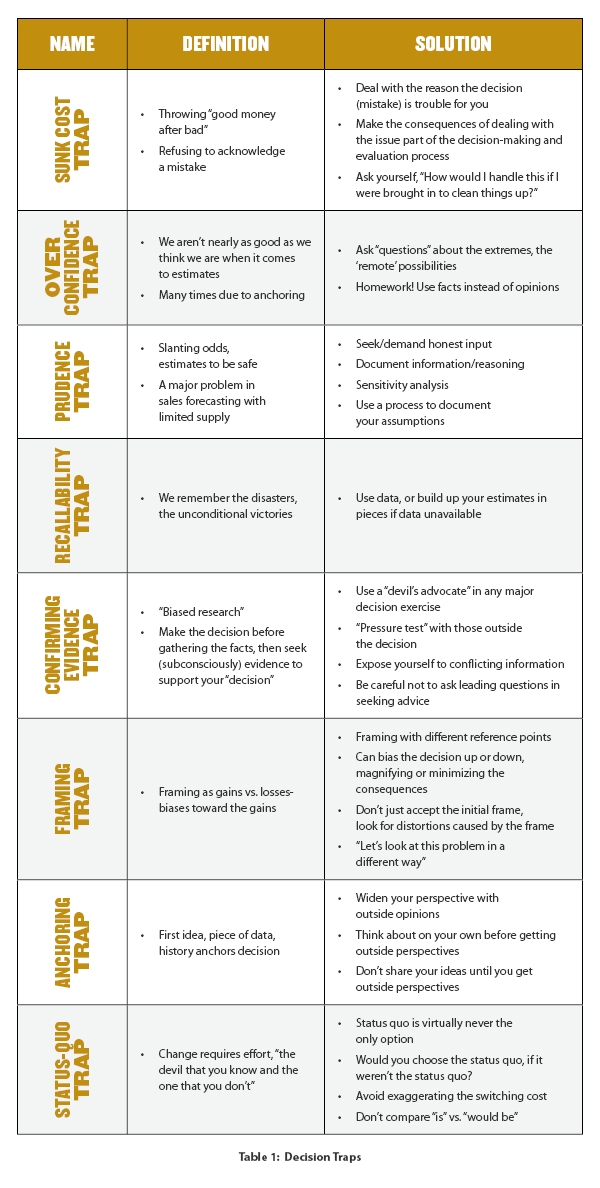

Hammond, Keeney, and Raiffa identify eight psychological traps that influence how our minds work in decision-making. Table 1 summarizes these traps and suggestions to limit the decision bias that result.

The potential implications of decision traps (and fatigue) for agribusiness firms are many. Consider the framing trap surrounding presentation of alternatives and the resulting impacts on your own and your teammates’ perspectives.

Let’s imagine that a large rainstorm is coming and there is $18,000 worth of hay at stake for your farming operation. One option provides a one-third chance of saving all the hay ($18,000 worth), but a two-thirds chance of saving nothing. We could re-frame the option and rightfully say that there is a two-thirds chance of losing all $18,000 of hay and a one-third chance of no loss.

Mathematically, the statements are identical, but they simply do not sound or feel the same at first glance. Never look at a problem from only its original frame. Consider taking a look from an alternative framing to determine how framing may be impacting your decision.

One must remain cognizant that we don’t ignore systemizing the decision process, including:

- Make sure you have carefully identified the problem or issue and not just a symptom.

- Dig for the root cause (perhaps use the “five whys” tool which is simple but impactful at identifying the root of the matter).

- Identify alternative solutions before selecting a path forward. Remember, you cannot implement a solution you have not considered.

But don’t rely on your systematic process to protect you from the traps and biases that can influence your analysis and final choice. Structure your thought processes to constantly review the potential traps you may fall into and continue to challenge your thinking in an attempt to minimize their impact. Finally, remember that in an uncertain world, bad results can happen to good decisions. In other words, just because you made the best decision possible does not guarantee with certainty a good outcome. The key is to use analytical procedures and decision-making structure to reduce the chances of making sub-optimal decisions and avoid knee-jerk reactions to poor outcomes.