The Difference Between Mentoring & Coaching

Reviewer

Reviewer

Dr. Pete Hammett, Visiting Professor

Articles

American Psychological Association: Monitor on Psychology, Your guide to mentoring – Everything you need to know to find and be a great mentor

Center for Creative Leadership: Mentoring first-time managers – Proven strategies HR leaders can use

Summary

Many organizations have put formal mentoring programs in place while other companies have sought to build a ‘coaching culture’. But honestly, is there really a difference between mentoring and coaching, or are mentoring and coaching the same thing with different names?

The short answer is that while coaching and mentoring are valuable talent management tools, they are, in fact, two distinct approaches to developing people. Over the next two Purdue Food and Agribusiness Quarterly Reviews, we’ll dive into these two talent management tools to provide a bit of clarity on the distinction between coaching and mentoring and how each might be best applied.

For our focus on mentoring, insights will be drawn from current research conducted by the American Psychological Association (APA) and the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL). First, a bit of history and definition.

What is a Mentor?

The term mentor comes from Greek mythology when Odysseus, who was heading off to the Trojan War, placed his trusted servant Mentor in charge of his son Telemachus. Over the years, the term mentor has been adopted to describe someone who imparts wisdom and shares knowledge with a less experienced colleague. Clearly, there is an appeal to the confidence Odysseus had in Mentor to entrust his son’s well-being and education to his faithful servant[1]. However, some suggest that the moment Odysseus entrusted his son into Mentor’s care, he limited Telemachus to only knowing what Mentor knew.

In contemporary settings, a mentor is someone who shares how they’ve handled past experiences. Likewise, mentors provide suggestions for how to become more effective in a specific skill or competency[2]. In essence, mentors impart their experiences and insights to someone in a 1:1 relationship.

What is a (Leadership) Coach?

We find the meaning of coach (an instructor or trainer) in the 1830 Oxford University Dictionary as slang for a private tutor who “carries” a student through an exam. Here again, we go back to Greek origins to find the word ‘agonistarkhes’ – meaning one who trains (someone) to compete in public games and contests.”[3]

A coach is someone who formally engages in a developmental relationship with a someone who aspires to enhance their leadership effectiveness, thereby enhancing the leadership capacity in their organization[4]. While successful coaching engagements rely on a strong 1:1 relationship between the coach and coachee, the coaching effort often extends to include feedback and insights from the coachee’s boss, direct reports and peers.

Again, both mentors and coaches are valuable tools in talent management, and both are focused on helping people grow and develop. However, there are key distinctions to keep in mind. Perhaps the best way to draw the distinction between a coach and a mentor is with a few examples. In this review, I will focus on mentoring.

Example of a Mentor

I would venture to say that most people in America know Al Roker – America’s most beloved weatherman. Roker forecasts weather as a regular fixture on the Today Show and reports on dangerous storms on NBC’s Nightly News. What most people don’t know is that Roker attributes his success to his predecessor, Willard Scott. Roker was a young weather forecaster when Scott reached out and invited him for a cup of coffee. Shortly after that first visit, the two met regularly, and the veteran Scott began imparting invaluable wisdom on the young Roker. In Roker’s words, “I couldn’t believe that one of the most famous weathermen in the country had taken an interest in me and my career.”[5]

What did Scott actually do to mentor Roker? Easy — he invested time in him. During this time, Scott shared what he had learned over years of broadcasting weather forecasts across America and wisdom he had gained being in front of a camera and interacting with people from many walks of life.

The story of Willard Scott and Al Roker helps clarify our understanding of mentoring. Just as in the Greek mythology, mentoring is when someone with greater experience, knowledge and skill imparts their wisdom and insight on someone less seasoned. The primary focus in a mentoring relationship is the personal and professional interests of the person being mentored (mentee), and the outcome of the relationship is (ideally) that the mentee gains greater skill and knowledge that is advantageous for them personally and/or professionally.

Why Mentoring is Beneficial

What does mentoring provide, and why would someone consider a mentoring program? According to Dr. Brad Johnson, professor of psychology at the U.S. Naval Academy, a good mentoring relationship or program will yield the following results[6]:

- Enhance a person’s skill in a particular competency

- Strengthen confidence

- Enable higher level performance, evident in better evaluations and career progression

- Achieve notable personal and career success

An interesting sidebar … most people who have engaged in meaningful mentoring relationships opt to mentor others as well. According to Dr. Johnson, “Good mentoring shapes not only the current generation, but future generations as well.”

Why Mentoring is Needed

The CCL’s report on mentoring first-time managers reminds us that most first-time leaders are underprepared for the challenges they will face. In the report, the CCL highlights the following:

- According to careerbuilder.com, 58% of new managers receive no formal management training or development at all before transitioning into leadership roles. Also, 20% of newly minted leaders do a poor job, according to their subordinates, and 26% of first- time leaders themselves felt they were not ready to lead others.

- A survey by Manchester International noted that 40% of newly promoted managers fail within the first 18 months.

- In 2012, Bersin reported that frontline supervisors receive the least amount of money and support in training and development dollars compared to all other managerial populations (e.g., mid- or senior-level executives).

Finding a Mentor

The challenge in finding a mentor and being a mentor has been compared to the challenge of finding someone with whom to build a meaningful relationship. It’s no wonder that a number of mentoring apps similar in nature to popular dating apps have surfaced. For obvious reasons, I’ll avoid the inevitable awkwardness of reviewing these mentoring apps. Instead, I’ll focus on how organizations can best leverage formal mentoring programs to effectively connect mentors and mentees.

According to the CCL, there are four key phases to effective mentoring programs:

- Mentors and mentees are nominated by their senior leaders and encouraged to participate in mentoring programs. During the initial discussion, program objectives are shared and potential goals of mentors and mentees are developed.

- Mentors and mentees are asked to select from several high-level organizational goals and add any additional goals they see fit. This ensures strong alignment to key initiatives occurring throughout the organization.

- Next, mentors and mentees are matched primarily to help mentees be successful in their new roles. In addition, mentors and mentees are matched for any “reciprocal knowledge” of different parts of the organization. For example, a new sales manager wants to better understand how to work with and leverage marketing resources, so he is partnered with an experienced marketing leader. The marketing leader also wants to better understand the changing market forces facing the sales function, so this would be a great match for the mentor as well. Mentors and mentees can also be matched when there is a mutual desire to gain insight from people of different cultures, genders, backgrounds and experiences.

- Finally, mentoring pairs are then selected and agreed upon by the mentor and mentee. Both mentor and mentee participate together in a mentoring training and orientation session with similar program aspects as outlined next.

The Mentoring Processes

Now that we understand why mentoring is needed and the framework for pairing mentors and mentees, the next question to consider is how the mentoring process should operate. Here, both the APA and CCL have insights to share:

- Be clear about the relationship – What do you want to learn? Be clear with yourself and your potential mentee about the parameters of your relationship. Spell out how long the mentorship will last, how often you will meet and the amount of time you’re prepared to offer.

- Be present – Mentors need to be mindful of the gift of time. Giving time to mentees is perhaps the greatest of gifts. A friend of mine came across a billboard in London that captures this point brilliantly: “Some people talk to you in their free time. Others free their time to talk to you. We would do well to understand the difference.”

An important aspect for ensuring an effective mentoring process is understanding the ethical principles of mentoring. Here again, we turn to Dr. Johnson from the U.S. Naval academy:

- Beneficence – Promote mentees’ best interests whenever possible.

- Nonmaleficence – Avoid harm to mentees (neglect, abandonment, exploitation, boundary violations).

- Autonomy – Work to strengthen mentee independence and maturity.

- Fidelity – Keep promises and remain loyal to those you mentor.

- Justice – Ensure fair and equitable treatment of all mentees (regardless of cultural differences).

- Transparency – Encourage transparency and open communication regarding expectations.

- Boundaries – Avoid potentially harmful multiple roles with mentees and discuss overlapping roles to minimize risk for exploitation or bad outcomes.

- Privacy – Protect information shared in confidence by a mentee and discuss all exceptions to privacy.

- Competence – Establish and continue developing competence.

How Organizations Can Strengthen Mentoring Programs

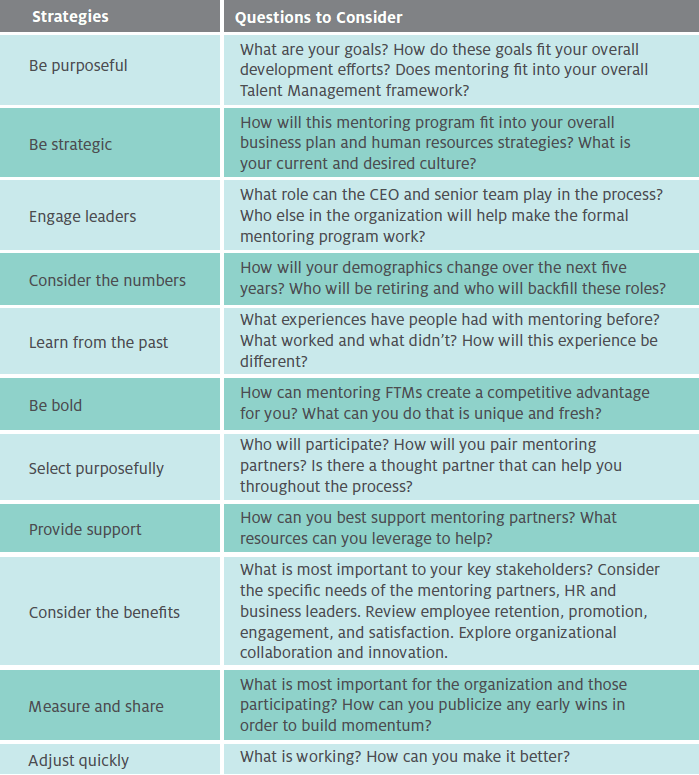

Mentoring programs are difficult to establish and more so to maintain. The benefits of an effective mentoring program cannot be overstated. That said, the negative impacts of a degraded or mismanaged mentoring program are significant. Therefore, it is critical that organizations invest the energy and resources into maintaining their mentoring programs. To aid in this maintenance effort, the CCL outlines the following strategies:

My Mentoring Experience

When I made VP at American Express, a number of unanticipated obligations surfaced, one of which being an expectation that I would be an active member on a local non-profit board. Actually, this was a pleasant surprise, and I found great satisfaction in the experience. Another obligation that was a bit intimidating was to be a mentor to an Amex colleague. I didn’t know anything about mentoring, having (at this point in my life) not had a mentor myself. I was given the option of identifying someone I wanted to mentor, or I could defer to Amex to select a mentee for me. Ultimately, I chose the latter option.

The mentee selected for me was Chris (*her actual name has been changed for privacy purposes). She’d been with Amex for eight years as a supervisor in customer service and had asked for a mentor to help her sharpen her awareness for how technology can enhance operations. With this being my area of expertise, Chris and I were matched.

Chris and I met for an hour every other week over the course of several months. I shared with her some of the process improvement projects we were working on, and she helped me understand how these efforts would play out in customer service. In time, Chris and I began to discuss other areas in which she wanted more insight, such as developing others and speaking more confidently with senior executives.

One visit, I was chatting with Chris about a business trip I had just taken to Amex’s technology hub in Phoenix. I mentioned that my usual hotel had suggested I stay somewhere else because it was hosting a spina bifida conference and movement within the hotel and elevators would be impacted. Because the hotel was so close to the Phoenix office, I decided to stay there anyway. I mentioned to Chris that while I was inconvenienced a bit, after watching the kids in wheelchairs effortlessly navigate the hotel, I left very curious about spina bifida.

Suddenly, our mentor/mentee relationship turned on a dime when Chris shared that she had spina bifida. I was lost for words. When I first met Chris, I noticed she walked with a slight limp, but I had simply assumed it was likely the result of an accident and didn’t really pay it any attention. For the next hour, Chris shared with me what spina bifida is and how it affects people. She then shared that the odds were high that most of the kids I saw in the hotel would not live past early adulthood. Chris shared how blessed she felt that her condition was very minor and that her future was bright.

I was never able to shake the image of the kids I saw in the hotel and wonder what was ahead for them. On my next stay at the hotel in Phoenix, I made it a point to speak with the manager and express my appreciation for their decision to host the spina bifida conference, knowing it would impact their other room reservations for that week.

I was profoundly grateful that Chris shared with me her experience and enlightened me on important aspects of spina bifida. I’d like to believe that she found our mentoring time helpful. I know I did, and I’m a much better person for our time together.

In the next Quarterly Review, I’ll focus on leadership coaching, further compare and contrast coaching and mentoring and suggest when and how to best utilize each.

Footnotes

[1] https://leadtogether.org/mentor-greek-mythology/

[2] Korn Ferry Leadership Architect

[3] https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=coach

[4] The CCL Handbook of Coaching

[5] https://www.today.com/news/al-roker-i-wouldnt-be-today-if-not-willard-scott-2D11600068

[6] https://www.apa.org/members/content/mentoring-booklet

RELATED POSTS:

Optimizing Sales Management: Knowledge, Coaching and Continuous Improvement

While we used to think that exceptional salespeople possessed an innate gift, recent data suggests the impact of today’s sales managers in nurturing and refining this gift to unlock its fullest potential.

A great moment for value-based sales in agribusiness

Value-based sales can empower companies to craft compelling value propositions, understand the customer’s business model and effectively communicate to stakeholders.

How can big data empower the development of new products?

Data is one of the most powerful resources for a company. It enables accurate decision-making and minimizes risk, ensuring greater revenue and sustainable growth.