Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve been working on new sales tools for managers who are trying to answer questions like: “How do I know whether I have a good salesperson in a difficult territory versus a poor salesperson in an easy one?”

If we only look at outcomes (revenue, market share), we can’t tell the difference. And if we want to understand a company’s sales strategy, we should be able to see evidence of it in results. We’ve made good progress on answering those questions (reach out to me if you’re curious), but one thing stands out clearly in the data: sales performance can vary dramatically, even within the same territory or region.

Having the privilege of working with the next generation of salespeople, I feel like I owe it to them to find ways to help them succeed. When we step back and look at the data, three things consistently emerge as non-negotiables for sales success today.

Focus on the customer

Salespeople need to put the customer first (or the distributor rep if you’re selling for a manufacturer), not on the product. The corollary is simple but important: the questions you ask matter far more than the answers you give.

“Customer focus” isn’t new. I’ve heard it repeated for the forty years I’ve been in sales. But for most of my career, if I’m being honest, the real priority was getting the sale. Customers mattered, but largely as a means to that end. The order of focus tended to be sales performance first, products second and customers third.

Those three elements still matter, but the order has changed.

Customers have to come first. Truly first. That means genuinely understanding what they care about and connecting my value to those priorities. My success can’t come before my customer’s success anymore. When we compare the impact of efforts spent trying to make ourselves successful versus effort spent trying to make customers successful, customers win every time.

In research we completed last year, top-performing sellers knew details about their customers’ businesses 10% more than their lower-performing counterparts. They also planned formally for customer interactions nearly 20% more often.

The era of trying to convince customers that my product is “the best” is in the rearview mirror. Products are too complex. Differences are too technical. And in most cases, there are dozens of viable solutions. Everyone has one. Everyone’s is the best, and every option involves trade-offs.

Learn where to put your resources, and where not to

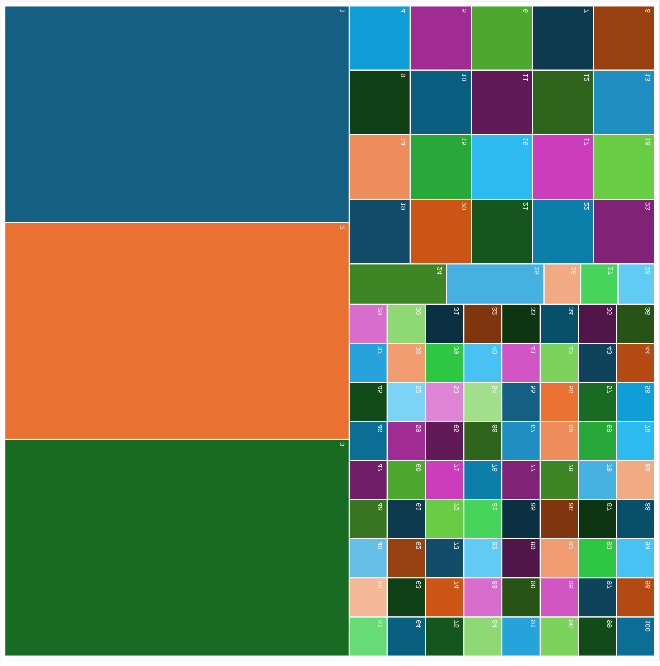

Across almost every organization, customer distribution looks roughly the same. A small number of customers account for a disproportionate share of a salesperson’s business. Meanwhile, a large number of customers each represent only a fraction.

The three customers on the left represent 50% of a sellers’ business. The 75 customers on the lower right each represent only 0.3% of the sellers’ business. Sales resources simply cannot be allocated equally. For the customers that drive the bulk of the business, the work doesn’t even resemble traditional “sales.” It’s account management. Performance metrics, planning, analysis and intentional engagement are not optional for those relationships.

The three customers on the left represent 50% of a sellers’ business. The 75 customers on the lower right each represent only 0.3% of the sellers’ business. Sales resources simply cannot be allocated equally. For the customers that drive the bulk of the business, the work doesn’t even resemble traditional “sales.” It’s account management. Performance metrics, planning, analysis and intentional engagement are not optional for those relationships.

For the 75 on the lower right, a seller can’t realistically allocate much individual effort at all. In between are customers who require intentional sales activity, but not at the same depth as top accounts.

This reality has implications. Instructions to “log every sales call in CRM” may not make sense across all customer segments. The planning and knowledge required to truly be customer focused needs to be directed to the right places, and we need to measure how well it’s happening. Not because the boss makes us, but because success with those customers depends on it.

At the same time, we can’t simply ignore the majority of customers. We need better ways to serve them efficiently. A territory strategy shouldn’t be defined only by how much we want to sell and to whom, but by how we allocate limited sales and technical time to support the farmers we serve.

Be humble and get good at asking for help

This one is fundamentally different from how many of were trained. Salespeople used to be taught that if they didn’t know the answer to a question, they should say, “I don’t know, but I’ll find out and get back to you.” Some were even taught never to ask a question they didn’t already know the answer to. That approach is the exact opposite of what effective selling requires today.

Very few people are experts in business management, genetics, commodity marketing, ecology, climate science, production science, equipment, finance, communication, policy, international relations, tax accounting, real estate management, negotiations, human resources, data analysis and risk management. And yet many farmers, especially those who account for the bulk of sales volume, have access to deep expertise in several of those areas.

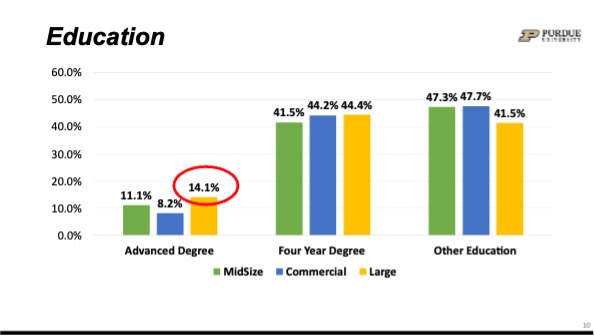

In our farmer decision-making research over the past year, we identified an emerging group of highly educated farmers earning under $350,000 in gross farm income. Smaller operations can still be highly sophisticated. Many farmers are deeply knowledgeable about topics they care about, and anxious or uncertain about others.

Farmer education by farm size

For a salesperson to walk onto a farm expecting to have answers most of the time is hubris.

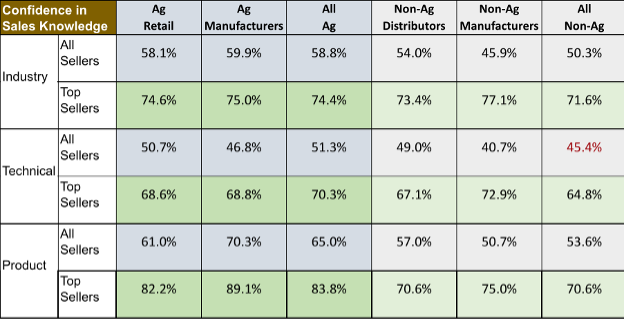

Not having an answer isn’t the exception anymore; it’s the rule. Restricting conversations only to areas where we’re experts limits customers to a narrow set of topics and limits our value. Confidence is strongly associated with sales success, but product knowledge is only one kind of knowledge that matters.

Salespeople must either have confidence in their knowledge of a lot of different areas or be good at handling situations where they may not be experts. Confidence by itself is probably not useful. False confidence (what I call confident ignorance) ultimately damages both the customer and the relationship.

What we teach today sounds different. A better response is: “That’s a great question. Let’s explore that a little. I’m happy to share what I know, which isn’t much, but tell me about your experience and concerns.”

Followed by: “I can see why that matters to you. I’m curious about it too. We have someone on our team who’s pretty deep in that area. Let’s learn about it together. If she doesn’t know off the top of her head, I know she’ll have someone she can connect us with.”

Confidence in sales knowledge

None of these non-negotiables are new ideas, but there’s a growing gap between the bulk of our customers and the bulk of our business. What once might have been considered best practices are now table stakes for serving the customers who matter most.