My mom is an independent insurance agent. She recently shared with my brothers and me that she had achieved renewals with more than 95 percent of her clients. I jokingly inquired, “Why not 100 percent?” Then my older brother chimed in, “Fire the bottom 10 percent of your staff until renewals are 100 percent!”

My mom is an independent insurance agent. She recently shared with my brothers and me that she had achieved renewals with more than 95 percent of her clients. I jokingly inquired, “Why not 100 percent?” Then my older brother chimed in, “Fire the bottom 10 percent of your staff until renewals are 100 percent!”

She is a staff of one, so I am not sure what that looks like.

My brother’s joke might sound a little extreme, but it is rooted in a real-world example. When Jack Welch was the CEO of GE, he asked managers to rank their employees annually. The bottom 10 percent were then encouraged to find employment elsewhere.

We recently had a GE leader share with us that the company has changed its performance management policies, and this particular practice no longer occurs. Instead, leaders help employees improve their contributions to overall company goals. In order to change the company mentality, GE’s entire performance management process had to change.

Setting goals and monitoring progress

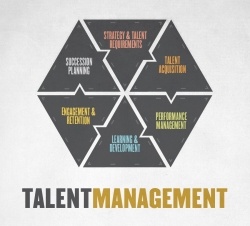

Performance management is the process of setting goals and monitoring progress towards them. In many large organizations, managers formalize this process with the annual performance review.

Food and agribusiness managers are reevaluating performance management systems. In the process, managers are shifting away from annual reviews, eliminating rankings of employees, focusing on improving the collection and use of data, and incorporating talent and performance management into the executive suite of decision-making.

The biggest change firms are undertaking aims to improve the quality and frequency of feedback on employee performance. There has been a stampede away from setting goals in January and then waiting until next January to monitor progress toward achieving those goals. Instead, managers are opting to help employees set goals that are of differing time horizons. Then managers collaborating with human resources to put systems into place that track progress quarterly, monthly, or even more frequently. The formality of the process is crumbling. Employees are more receptive to frequent, less formal feedback. Employees are able to course correct more quickly and focus on improvement.

Firms are also doing away with rankings of employees as the basis for determining pay raises and promotion decisions. Instead, managers are focusing on the career goals of the individual and aligning them to company goals. The most effective managers provide mentoring to employees who are underperforming. Often managers are responsible for removing hurdles so that employees can improve and grow. The new systems focus on understanding each individual’s contribution to the team and company efforts and reward the employee befitting that.

Progressive Performance Management

Progressive firms are on the cutting edge of collecting and using data to improve performance management. As GE moved away from the old model, it opted instead to collect frequent feedback on employees and managers. GE developed an in-house app to facilitate quick, real-time reporting of progress. Employees often leave meetings typing into the app what peers should continue doing and consider changing.

Progressive firms are also moving away from HR as an administrative center that processes hiring contracts and benefits to one that is a strategic partner in executing firm strategy through employees. Purdue research shows that in agribusiness, firms rate poorly on performance management when the HR function is entirely administrative. Employees rate firms as doing well on performance management when they view HR as a strategic partner. It is when HR collaborates with managers in other functional areas that performance and talent management have the biggest payoff. In this system, HR creates systems that empower managers to be successful leaders.

Managing Talent to Win

Performance management is just one of the elements of overall talent management that leaders often struggle to get right. Things such as succession planning, talent acquisition, engagement and retention and more come with their own unique sets of challenges.

Purdue University’s Center for Food and Agricultural Business recognizes these challenges and is here to help managers succeed in the talent management realm. June 25-27, we will offer Managing Talent to Win, a professional development program focused on helping managers at all levels attract, support and retain quality employees who will help their companies continue to improve.

Learn more at http://agribusiness.purdue.edu/programs-workshops//managing-talent-to-win.

: