Reviewer

Dr. Pete Hammett, Visiting Professor

Articles

Teaching Employees How to Receive Feedback: A Preliminary Investigation

The Impact of Authority Relations and Feedback Delivery Method on Performance

Journal

Journal of Organizational Behavior Management

Prior to joining Purdue University as a visiting professor, I was the head of human resources at OGE Energy Corp. Heading HR for nearly 10 years was without a doubt the most rewarding and most difficult role I have ever held. The rewarding nature of HR lies in partnering with people in managing their career, and the difficult part lies in dealing with them when they are at their worst. In my early HR days, I would be floored by some of the shenanigans people would take part in doing. At one point, I was tempted to create a Guide for Staying Out of HR’s Doghouse, which would include tips such as:

- Never send an email to your boss or coworker when you are mad, especially if you have been drinking.

- Do not use company time, resources or property to supplement your side business, especially if the side business is illegal.

But the most frustrating aspect of HR is managing conflicts that regularly surface when people get cross with each other. Misunderstood intentions, misspoken words, inconsiderate actions and perceived slights foster ill-tempered reactions and eventually lead to direct confrontation and/or formal complaints. What’s worse is that nearly all of these conflicts could have been resolved if people would simply talk to one another.

If I were asked what the one thing organizations could do to improve overall employee morale, productivity and engagement is, my response would be to develop a culture that places a premium on effectively giving and receiving feedback.

Summary

Feedback is like the stock market — we understand how it should work in theory, but in practice, we are less confident. In normal language, feedback is about letting the people you interact with know how they’re doing, encouraging them when they’ve done something well and offering helpful advice when something wasn’t so great.

When someone steps on our toes, we know we should say something, but we’re more likely to ignore the offensive and fume inside. Why do we do this? Do we like being mad? Are we so conflict-avoidant that ignoring the offense is more compelling than dealing with the problem? Two recent articles in the Journal of Organizational Behavior Management help us answer these questions.

In The Impact of Authority Relations and Feedback Delivery Method on Performance, the authors remind us that “feedback can vary widely in terms of the conditions under which it may be delivered, who is delivering it, how it is being delivered, and when it is delivered.” With this in mind, their study sought to highlight the influence of two factors on the effectiveness of giving feedback: 1) the level of the person proving feedback (e.g. boss, supervisor), and 2) how the feedback is provided (in-person, phone, email).

Results[1] of the study found that when delivered by an authority figure, both in-person and distance-delivered feedback resulted in improved performance; however, only face-to-face feedback resulted in improved performance with a non-authority figure. For me, these results pass the sniff test. If your boss gives you feedback, you typically get right on it regardless of if it was delivered in-person, on the phone or by email. However, if the same message comes from a peer or colleague, we are more likely to view it as criticism rather than helpful advice, especially if the message is not given in person.

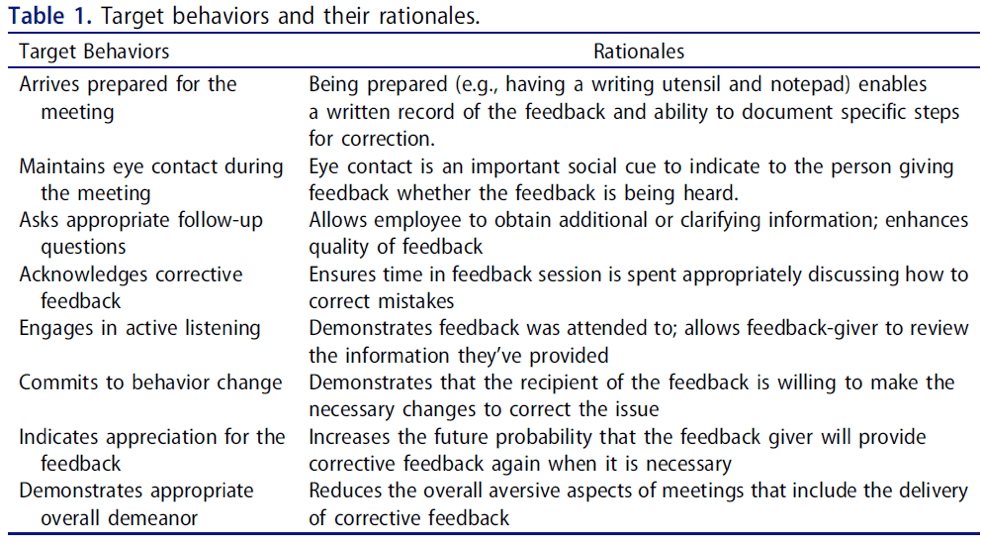

In Teaching Employees How to Receive Feedback: A Preliminary Investigation, researchers outlined a set of skills that should ideally be exhibited by an employee when receiving verbal feedback. These skills focused on social interactions such as maintaining eye contact and active listening (Table 1). The study focused on the impact of developing employees in how to receive feedback by focusing on these social skills.

Results from the study suggested that employees trained on leveraging the target social behaviors where more capable of applying feedback, and thereby increase overall performance.

I’m a bit lukewarm on this study, mainly because of the small number of observations (three entry-level administrative staff members). That said, the premise for the study is sound; just as we need to develop our ability to provide feedback, we also need to develop our ability to receive it. Likewise, listening, asking questions and appreciation are solid responses when receiving feedback.

What this means for Food and Agricultural Business

Recent events and unprecedented circumstances brought on by COVID-19 have been deeply felt by the food and agribusiness industries — and by most industries for that matter. In our current environment, it is no surprise that tensions may be higher and margins for error may be tighter. For these reasons, the art of effectively giving and receiving feedback is all the more important.

Giving Feedback

When giving feedback in your firm, be sure to consider that providing feedback is not for the faint of heart. It takes time, courage and compassion to engage in this awkward and, at times, complicated endeavor, and delivering effective feedback takes practice…lots of practice.

Many misperceptions exist in regard to giving feedback, not the least of which being that it is only for corrective/developmental action. Feedback should be both affirming and developmental. In fact, my friends at the Center for Creative Leadership suggest a ratio of 4-to-1 — four positive/affirming messages for every developmental message.

From experience, I have found that providing feedback in-person is a best practice, especially if it is developmental. In times when in-person feedback is not practical, a phone call is the next best option. I’m not a fan of providing corrective feedback with emails, but I understand when logistics and timeliness make it the best option.

An often-overlooked fundamental principle for providing effective feedback is the role relationships play. For most individuals, a good relationship and rapport are necessary for feedback to be effective. Without a good relationship, feedback is, at best, a hollow flattery, or at worst, an unwelcome criticism. To make my point, you don’t need a strong relationship to tell someone their shoe is untied, but a strong relationship is advisable before you tell someone their zipper is down.

The second principle for feedback is a clear and validated understanding that it is both sought and welcomed. Most people welcome feedback, but a word of caution is noteworthy. We all know folks with an over-inflated ego — a narcissist to be more descript. Narcissist egos inhibit them from accepting any critical feedback. In fact, if any personal shortcoming is pointed out, narcissists will be quick to deflect to someone they feel is worse than them. For a narcissist, their status (power and influence) is their strength and feedback is their kryptonite.

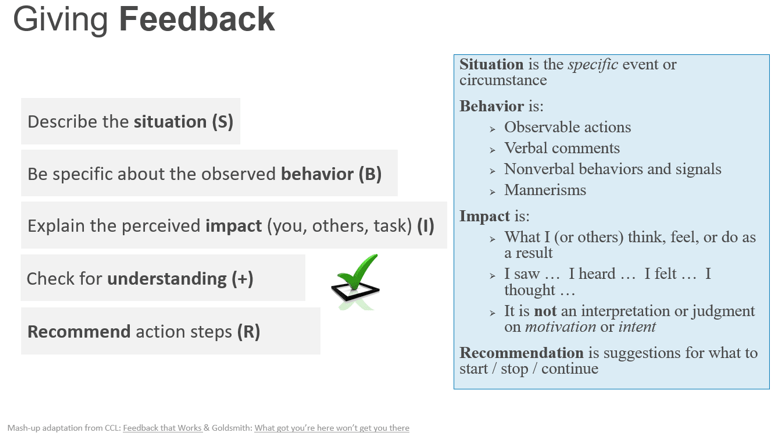

From 2009-2012, over 500 leaders at OGE Energy Corp. participated in a two-year leadership development program. Of the topics covered in the program, giving and receiving feedback was a central theme. Below is the feedback used, which could be helpful for you to implement in your organization. It is a combination of work from The Center for Creative Leadership and Marshall Goldsmith.

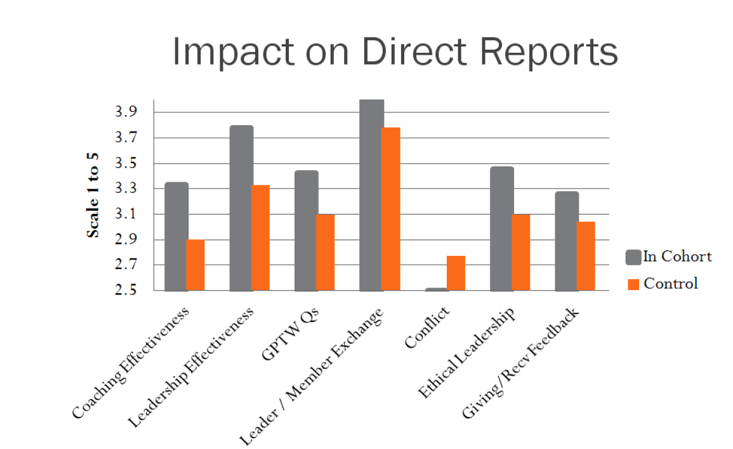

In a deferred impact study on the effectiveness of the OGE Energy Corp. leadership program, post-doctoral industrial and organizational psychologists from Oklahoma University developed the chart below reflecting the effectiveness of leaders in the leadership program (in cohort) versus leaders who had yet to enter the program. The positive impact of giving and receiving feedback can clearly be seen (as well as dealing with conflict).

Receiving Feedback

A major reason we avoid sharing feedback is the concern of how someone will react. Will they be angry? Will they think you’re out of line? Will they throw things in your face and give you a hard time? If you want to develop a culture that places a premium on feedback, intentionally focus on helping people respond well when receiving it.

As an example, I once worked with a manufacturing CEO on developing her leadership team. An exercise we did was go around the room and speak to each person’s strengths and development opportunities. In planning for the exercise, I met with the CEO and suggested that she go first and ask her leadership team for feedback. Since I had been working with her for a while, I suggested I would be the first to give her feedback. I then offered suggestions for how she should respond to the feedback, most importantly by expressing sincere appreciation.

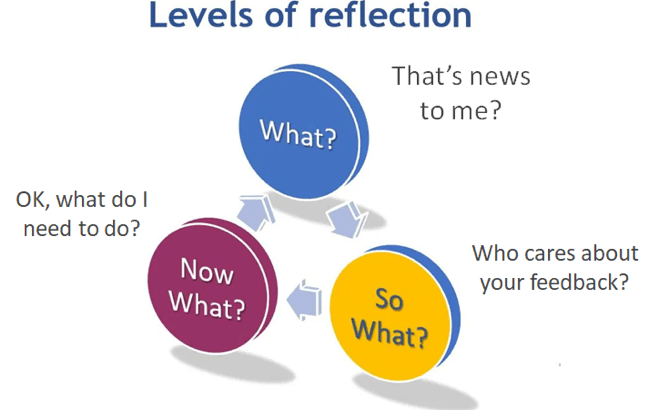

When people receive feedback, especially feedback that’s hard to hear, there are three reactions they go through:

- What? – Surprise and dismay (This is news to me!)

- So What! – Defensive or resistant (Who cares what you have to say?)

- Now What. – Acceptance (You’re right, and I need to work on this.)

The four best responses to receiving feedback are:

- Say thank you, show appreciation and acknowledge the courage it took for someone to share this with you.

- Ask for clarification if you need it, but be mindful to not be defensive.

- Keep in mind that perception is reality. You may not agree with the feedback per se, but you cannot argue with someone else’s perception.

- Ask for continued feedback.

Both now and in the future, I wish you the very best in practicing the fundamental art of giving and receiving feedback. With time and effort, it will continue to become more natural. Thanks for reading!

[1] As we reflect on how these research findings might translate to the business world it’s important to note that the study was conducted with 120 undergraduate and graduate students from a university in South Korea.