The first time I recall personally experiencing talent management was when I was about 14. I was working for my grandparents on their nine-hole golf course, named Cecelia’s, that had been built atop 40 acres of prime southern Wisconsin farm ground. Built during the 1988 drought, people thought my grandpa was crazy for doing so. Despite early setbacks and patches of brown grass that first year, that course turned to green—literally and figuratively.

The first time I recall personally experiencing talent management was when I was about 14. I was working for my grandparents on their nine-hole golf course, named Cecelia’s, that had been built atop 40 acres of prime southern Wisconsin farm ground. Built during the 1988 drought, people thought my grandpa was crazy for doing so. Despite early setbacks and patches of brown grass that first year, that course turned to green—literally and figuratively.

But I digress.

I was spending the summer away from my parents’ dairy farm. Grandpa knew that I knew how to drive a tractor, so he set me on his Ford 2120 and instructed me to go pick up golf balls from the driving range and mow it at the same time. I had never used the contraption that attached to the front of the tractor to pick up balls. It was slightly narrower than the gang mower that followed behind, which meant that on occasion, range balls would fly up from the reel mower.

So far, so good.

I noticed the fuel gauge getting low. I unhooked the ball picker and the mower and headed back to the shop to fill up. Wanting to impress Grandpa, I raced back to the driving range to finish up. As I neared completion, the tractor seemed to act up. It was losing horsepower and I couldn’t figure out why.

I cannot recall if I put gas in the diesel or diesel in the gas, but I screwed up. Grandpa was seething underneath, but his first action was to repair the tractor. After he drained the engine, fuel lines, and tank and worked some mechanical magic, it appeared the tractor would be okay. We headed to the clubhouse to get lunch. Just as I was getting ready to bite into my hamburger, Grandpa swatted the back of my head. “That’s for screwing up,” he said. Then a second later, he swatted me again. “And that’s for your next screw up.”

Back to business

It seems that this is how talent management tends to go on many farms and in many food and agribusiness firms today. We’ve done a job for so long, we’ve forgotten what it’s like to not know how to do it. When the boss ahead of us gets promoted, we move up too. Then we hire replacements, “set them on the tractor” and tell them to go do good things. As long as the employee does good things, we stay out of the way. When mistakes are made, we scramble to fix them and admonish the employee to do it right next time.

Today’s complex job responsibilities require us to approach talent management differently. When you’re at the end of a field with a hay rake in tow, it probably would take just one or two passes before getting a sense of how to complete the task. Likewise, most of us would probably figure out how to get the milk calves fed after just a day or two of being shown how.

These task-oriented jobs are very different than the demands modern food and agribusiness professionals face. Talking with just one or two customers will not prepare a salesperson well for a season of relationship development. Working with an internal team to develop a full-farm cropping plan is not something you become an expert at after working on one (or even a dozen).

A deeper understanding

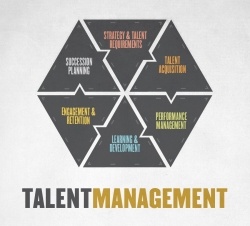

At the Center for Food and Agricultural Business, we started to deepen our understanding of talent management. We have identified six areas of focus (see figure). We have begun to pose questions that include:

- Can we get even more out of employees by mentoring them at times both good and bad?

- How do we get maximum engagement among employees and retain our best?

- Is there a more effective approach to talent management?

Many firms have ditched the annual performance review for more constant, ongoing feedback. It isn’t because agribusiness professionals are making mistakes that much more often. Rather, many managers see opportunities to accelerate the development of employees to their fullest potential.

Frequent dialogue not only identifies challenges earlier on, but also provides guidance regarding the strategies that are most likely to succeed. The complexity of modern roles in agribusiness firms makes learning by trial and error time consuming and costly.

Engagement and performance

Studies have identified employee engagement as a key driver of team and firm performance. Employee engagement embodies a symbiotic relationship between employee goals and firm goals. Engaged employees are motivated to come to work every day and make decisions to further the firm’s interests.

At Cecelia’s, management drove engagement primarily by hiring family and family of close friends, and providing free meals. In agribusiness firms, free lunch might be nice, but the connection to engagement might be tenuous. Instead, management must share inspiring visions and missions, emphasize the importance of an employee’s role in achieving that vision, and detail how achievement in current roles can lead to future opportunities with the firm.

So, is there a more effective approach to talent management? Yes. In fact, there is an entire science dedicated to talent management. Books such as One Page Talent Management by Marc Effron and Miriam Ort are able to point managers in the right direction when it comes to the science.

The concepts covered in Money Ball regarding how to use metrics to predict individuals’ performance are gaining use in firms. Companies like Google are collecting data on the effectiveness of managers and equipping them with the tools to close skill gaps. In the competitive agribusiness marketplace where everyone boasts their employees are their biggest assets, it’s time to bring these tools to the forefront.

: