Article

Work curiosity: A new lens for understanding employee creativity. Yu-Yu Chang and Hui-Yu Shih

Journal

Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 29, No. 4. December 2019

Reviewer

Dr. Michael Gunderson, Director and Professor

Summary

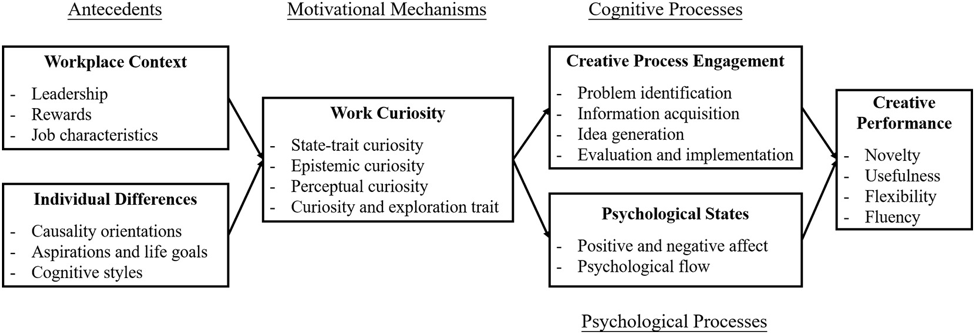

This Quarterly Review article is different from others I have done in that it is mostly theoretical. The authors use observed psychological research to build a model of molding curious employees in a firm (see figure below). The authors also link employee curiosity to employee creativity.

The figure is full of some jargon, but it is simple with a little digging. Chang and Shih define curiosity as “… the desire for new information, knowledge, experiences, or sensory stimulation to resolve gaps or experience the unknown.”

Motivational Mechanisms

The authors note research has identified different types of curiosity: state-trait, epistemic, perceptual and the curiosity exploration inventory. The research has also defined what motivates curiosity. Generally, it suggests that curiosity is motivated by either a desire to move away from an undesirable state (state curiosity, D-type curiosity, specific curiosity, and stretching curiosity) or the natural inclination to move toward a more exciting, new state (trait curiosity, I-type curiosity, diversive curiosity, embracing curiosity).

Antecedents

Thus, workplace context and individual differences can influence work curiosity. Here, the workplace context is free of jargon. For individual differences, causality orientations are autonomous choices made based on our goals and needs. Cognitive styles is jargon for how willing someone is to move away from the agreed-upon way of doing things. Some people are more risk-averse in their decision making than others.

Cognitive and Psychological Processes

Once the antecedents and motivational mechanisms are in place, the authors suggest how an employee might begin to engage and react to being curious. Curious employees will naturally acquire new knowledge, identify problems, generate solutions and drive change. Curious employees also tend to be happier and have greater energy relative to less curious peers.

Creative Performance

Finally, if a firm values creativity, the authors establish the link between these four factors (Motivational Mechanisms, Antecedents, Cognitive Processes and Psychological Processes) and creative performance. In the knowledge economy, creative performance is an important differentiator of successful firms.

What this means for Food and Agricultural Business

What adage first comes to mind when you hear the word curious? If you are like me, it’s “curiosity killed the cat.” How many of our agricultural and food businesses cultivate a culture that thrives on this adage? Specifically, how many agribusinesses are averse to trying new ways of doing business? Perhaps the firm has been successful sticking to time-tested policies and procedures. Some sprawling firms can create internal bureaucracies that stifle curiosity.

There is a variant of the adage that includes the rejoinder, “but satisfaction brought it back.” That is, the nine-lives of a cat exist because satisfying the curiosity resurrects it. Maybe this longer version of the adage is what agribusinesses should heed. That is, curiosity is necessary to reinventing a stagnant firm.

Other leading thinkers have a much different perspective on curiosity than the adage. For example, Einstein wrote, “The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existence.” My own teaching philosophy has been guided by Plutarch’s observation that, “The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.” And Eleanor Roosevelt opined, “I think, at a child’s birth, if a mother could ask a fairy godmother to endow it with the most useful gift, that gift would be curiosity.”

As leaders, can we be that fairy godmother endowing our teammates with curiosity? The research identified in the article clearly points to actions firms can take to influence employees’ curiosity. Chief among those factors is the role of leadership.

Leaders will have to navigate carefully between D-type/specific and I-type/diversive curiosity. Back to the adages – D-type/specific curiosity is illustrated by, “necessity is the mother of invention.” A part of leadership is aligning employees’ curiosity and creative behavior with the organization’s vision and goals. To some extent, employees have to feel comfortable in their roles, but leaders also use incentives and rules to direct where creative efforts are concentrated. This helps with specific curiosity, but doesn’t necessarily help with curiosity for curiosity’s sake.

Leaders looking to cultivate curiosity about what could be should encourage employees by sharing power and allowing for decisions to be made as close to the customer or problem as possible. The leader should emphasize the significance of the work and reduce the burden of company policy on team members. Particularly among younger workers known for wanting to contribute to ambitious visions, leaders might want to use this empowering leadership to rouse curiosity.

Similarly, the leader must carefully navigate between giving team members a challenging work load with significance and completely overwhelming employees. As it relates to encouraging curiosity about what could be, leaders should give team members discretion over what work has the most influence over outcomes. Leaders should also give plenty of flexibility on the means and times when goals are achieved. The leader must, however, help the employee manage their time. When a team member becomes overwhelmed and the time pressure too great, employees might revert back to doing what they know.

One tool that I have found useful in navigating some of these trade-offs is the book, The Coaching Habit. It has been a useful instrument that gives seven guiding questions for conversations with employees. When we shift from being the boss to being a coach, the interaction changes substantially. The seven essential questions help employees identify problems, assess trade-offs and naturally use curiosity to solve their own problems.

Another consideration for the leader is that employees have varying predispositions to curiosity. Some team members will more naturally deal with change. There are several change style assessments that a leader of a large team could use to guide them. Furthermore, some employees will be more naturally rewarded simply by acting on their curiosities. Some of their peers might be more motivated by bonuses and recognition. I don’t have a book suggestion to address this, but offer that this is best achieved with some meaningful dialogues over time.

Finally, creativity might be valued in the firm, but it is also likely a difficult item to measure, which brings me back to one more adage (I promise) — Einstein’s observation that, “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.” Creativity is squishy – you know it when you see it. It might be useful to categorize creativity using the authors’ suggested process engagement opportunities: (1) problem identification, (2) information acquisition, (3) idea generation and (4) evaluation and implementation. By beginning to categorize the creativity leaders observe, they might also start to effectively measure it.

One conclusion clear from the literature is that when a leader successfully navigates the trade-offs to establish a culture of curiosity and creativity, employees experience greater happiness and engagement in their jobs. Building a learning culture is essential for firm success in the dynamic food and agribusiness marketplace. Just as I was writing this, Dean Foods shared that it was filing bankruptcy. I wonder if the organization might have positioned itself differently if a culture of curiosity existed. Would the employees have been more eager to react to a noticeable 40-year decline in per capita milk consumption? I’d be curious to know your thoughts. Tweet me at @docgundy.